By Ikedi Ohakim

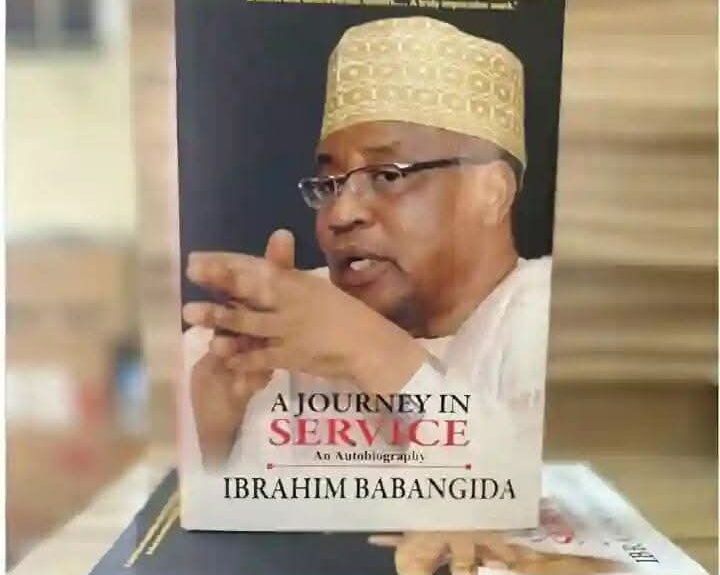

It is not surprising that the revelations and admissions by former military president, General Ibrahim Badamasi Babangida (IBB)., in his recently released autobiography, A Journey In Service, has elicited a lot of reactions from virtually every section of Nigeria and her citizenry. The thrust of most of the reactions is that he made his revelations very belatedly, after the nation had gone, full cycle, through the agony of some of his actions while in office, key of which is the annulment of the June 12, 1993 presidential election. In my opinion, however, it is wrong to accuse IBB of coming with his revelations belatedly simply because of June 12. IBB in his book raised other critical issues that transcend June 12. As far as I am concerned, he came up with them at the most appropriate time since it gives us a larger ambience to interrogate other acts of perfidy that were committed against Nigerians and their country before and after June 12.

Minus the fact that many Nigerians miss the amiable and very large-hearted Moshood Abiola – who perhaps would have still been alive today but for that annulment – I believe that the nation has since put June 12 behind it; especially after the regime of President Muhammadu Buhari wisely decided to recognize him as a former president. We should count ourselves lucky that God kept General Babangida alive up till now. IBB would have had nothing to lose if he had preferred to keep mute till the Almighty Allah takes him away. In other words, Nigeria as a country is the beneficiary since, as I have already pointed out, the book has armed us with materials for a more transcendental interrogation of our collective existence.

So, much as the reawakening of the emotions over June 12 by IBB’s book is quite understandable, I think that what matters now is to immediately follow up with the revelations of the retired General. We have to immediately embark on a journey towards a true and final reconciliation; to which we have paid lip service over the years. There was an attempt at that through the Oputa Panel but the opportunity was bungled. In the light of what we now know, thanks to Babangida’s book, we should avail ourselves another opportunity and with all alacrity this time around.

In making this submission, I am encouraged by the fact that the fellow currently at the helm of affairs, President Bola Tinubu, has demonstrated a tremendous flair for getting at the root of issues. Therefore, apart from the imperatives of his bold and courageous economic reforms, I think that providence is also saddling him with the responsibility of building a new nation.

Let’s take the civil war, especially the circumstances that led to it. Take specifically the January 15, 1966 military coup and the counter coup of July 29, 1966. Even though a lot has been written before now about the two military coup de’tats that led to the war, I am of the opinion that IBB’s narration is the one we have been waiting for. Take the matter of whether or not the January 15, 1966 coup was an “Igbo coup”. I am of the strong belief that as far as majority of Nigerians are concerned, Babangida’s book has finally laid it to rest. Contrary to what have been bandied for nearly the past six decades, Babangida’s book has shown that it was not an “Igbo coup”, pure and simple.

This was how IBB put it: “… as a young officer who saw all this from a distance, probably, ethnic sentiments did not drive the original objective of the coup plotters. For instance, the head of the plotters, Major Kaduna Nzeogwu, was only ‘Igbo’ in name. Born and raised in Kaduna, his immigrant parents were from Okpanam in today’s Delta state, which in 1966, was in the mid-west. Nzeogwu spoke fluent Hausa and was as ‘Hausa’ as any! He and his original team probably thought, even if naive, that they could turn things around for the better in the country … It should, however be borne in mind that some senior officers of Igbo extraction were also victims of the January coup. For instance, my erstwhile commander at the Reconnaissance Squadron in Kaduna, Lt-Col. Arthur Chinyelu Unegbe, was brutally gunned down by his own ‘brother’, Major Chris Anuforo in the presence of his pregnant wife … it should also be remembered that some non-Igbo officers like Major Adewale Ademoyega, Captain Ganiyu Adeleke, Lts Fola Oyewole and Olafimihan, took part in the failed coup. Another officer of Igbo extraction, Major John Obienu, crushed the coup”.

Babangida further pointed out that “those who argue that the original intention of the coup plotters was anything but ethnic refer to the fact that the initial purpose of the plotters was to release Chief Obafemi Awolowo from prison immediately after the coup and make him the executive provisional president of Nigeria. The fact that these ‘Igbo’ officers would do this to a man not known to be a great ‘lover’ of the Igbos may have given the coup a different ethnic coloration…”

I am relieved by Babangida’s disclosures. They have removed a load on my head with the realization that we can now bring a closure to one particular issue that has militated against our efforts at building a united nation since after the civil war. Let’s not make any further mistake about it, the wrongful dubbing of the January 15, 1966 coup as an “Igbo coup” is at the very heart of our problem as a nation. That falsehood was what led to the second coup of July 29, 1966 and the subsequent pogrom which Babangida in his book described thus: “…the most horrific killing of the Igbos occurred in different parts of northern Nigeria on September 29, 1966… the killings were frightening” (page 63). If northern elements – both civilian and military – took a revenge on Igbo civilians, whose brothers in the army allegedly staged a coup that led to the death of several of their political and military leaders, the anger was total among the Igbo back home.

Stories of the pogrom were quite disheartening. I have a personal one. A man, who was popularly known as Bekee in my home town, Okohia, had his pregnant wife killed in his presence; her stomach ripped open and the unborn baby brought out from the womb and smashed. Although Bekee managed to escape and return home, he could not survive the trauma of that experience. The story angered the youths in my area as a result of which several of them – including my very self – rushed to get enlisted into what was then known as the Boys Company, a branch of the Biafran army. Over 70 per cent got perished in the war.

Since after the war, caused basically by the falsity of an ‘Igbo coup”, the Igbo have been at the receiving end; and which is why there is a subsisting agitation for a separate country. What Babangida has done is calling on the leadership of the country for a final closure to what seems to be an animosity in perpetuity. If we must mobilize the entire citizenry for nation building, there must be reconciliation. So, rather than doubt his sincerity, Nigerians should see in what IBB has done through his book as a grand opportunity to pursue a new dawn. But for that to happen, some of the major dramatis personnea in that saga should take a cue from there and similarly tell the nation all that they know about that dark era of our history. Take General Yakubu Gowon, for example, who, more than any other living Nigerian, was most central in the events that ensued after the ‘Igbo Coup’.

Essentially, I would like that General Gowon address Nigerians on the Aburi Accord; why it failed and which some narrators, including Babangida, cite as the final straw that broke the Carmel’s back; that is, the thing that finally led to the thirty-months long civil war. A well-known angle to the story has it that Lt-Col Yakubu Gowon – as he was then known – as head of state of Nigeria reneged on the agreements in the Aburi Accord upon the advice of Northern political leaders who told him that the Accord – which was that Nigeria should go for a structure of a loose federation – was not in the interest of the North. Let’s take a look at the insights provided by Babangida in his book:

“The emergence of Lt-Col Gowon as the new Commander-in-Chief of the Nigeria Armed Forces marked the beginning of the tension between Gowon and Lt-Col Emeka Odumegwu-Ojukwu. … Ojukwu rejected Gowon’s emergence as Head of State, insisting that in the absence of Aguiyi-Ironsi, the most senior Nigerian Army officer in the person of Brigadier Babafemi Ogundipe, should be Head of State and Commander-in-Chief”. But that was not to be; and tension rose. According to IBB, it was under these circumstances that Lt-General Joseph Arthur Ankrah, then Ghana’s head of state, “stepped in by suggesting a neutral and safe venue for an actual Reconciliation conference between Ojukwu and the federal government”. Babangida further wrote that that intervention by General Ankrah led to the famous Peace Conference in …Aburi between January 4 and 5 1967 and which resulted in the “famous Aburi Accord”. But that was where the story ended.

Hear IBB: “in the absence of fully published records from the federal government regarding what transpired at the Aburi meetings, the details of what happened HAVE (emphasis mine) remained speculative. While the published accounts of the eastern Nigeria delegation insisted that an agreement for a loose Nigerian federation was agreed to, the federal government claimed that the agreement reached was understood and seen within the framework of a united Nigerian state… These differences in interpretations were the final trigger for the outbreak of the Nigerian Civil war”.

Since Ojukwu is no more, it is to Gowon, who was present at the public presentation of Babangida’s book – and even made a speech – that Nigerians should now turn to with the question: “What happened?” Why was the Aburi Accord not implemented; or why did the federal government which he led choose to wallow in ambiguity over the contents of the Accord as clearly stated by IBB? Why was Brigadier Ogundipe, who was the most senior army officer then, not allowed to take over as head of state and commander-in-chief? Fast forward to 1976, after the assassination of the then head of state, General Murtala Mohammed and how almost effortlessly the military hierarchy settled for the then Lt. Gen. Olusegun Obasanjo, who was Mohammed’s second-in-command, to take over as head of state and commander-in-chief.

Babangida recalls: “We knew it would be either General Obasanjo or General Danjuma since as Lt. Generals, they were the most senior… the pendulum swung in favour of General Danjuma at the start of the deliberations. Everyone present, including Obasanjo, thought Danjuma should take over. But somehow, Danjuma cast his lot for Obasanjo, insisting that as Mohammed’s deputy and a ‘senior’ Lieutenant-General, Obasanjo should succeed Murtala Mohammed. Obasanjo refused and offered… to retire from the army to enable Danjuma to emerge as head of state. There appeared to be a momentary stalemate. But that soon faded away. Faced with the insistence of Danjuma, everyone caved in and Obasanjo accepted the challenge to succeed Murtala”. Going by the above, was Ojukwu, not vindicated on his stance on Ogundipe in 1966?

The next among the resource fellows in our proposed final reconciliation conference would be former civilian president, Dr. Goodluck Ebele Jonathan. I believe that many Nigerians are aware that in a book released earlier, BOLD LEAP, an autobiography of Senator Chris Anyanwu, she made a revelation which has remained a subject of discussion throughout the country in the past two months or so. Senator Anyanwu had in her book claimed that she got approval from President Jonathan to call in the military to intervene in the 2011 governorship election in Imo state.

On page 470 of her book, Anyanwu narrated how, at a meeting with Dr. Jonathan in his house in his home town, Otueke, in Bayelsa state, the then president, said “Ok” to her proposal to mobilize the military to Imo state in order to stop me from rigging the governorship election. And as is well known, the military invaded the state in a Gestapo style and unleashed terror on the electorate. The question Nigerians have been asking since after that revelation is, assuming that it was true that I wanted to rig the election, was drafting the military into an electoral process the best way to stop me? Up till this moment, Dr. Jonathan and his handlers are yet to respond to that claim by Senator Anyanwu, a claim that clearly defamed him and poured red ink on his democratic credentials. Like Gowon, Jonathan was present at the launching of IBB’s book. So, to him (Jonathan) also should be directed the question: “What happened”?

However, he, Jonathan, does not have the liberty of waiting, like IBB, for thirty two years; for the simple reason that Nigerians are eager to come to a closure to the practices and individual idiosyncrasies that constitute stumbling blocks in our match to an enduring democracy. Even so, Babangida’s ‘crime’ is perhaps more pardonable since it was committed in the context of a military regime with June 12 epitomizing the determination of Nigerians to end it once and for all. On the other hand, the perfidy that occurred in Imo in 2011 came eighteen good years after Nigerians had decisively won the battle to install an enduring democracy.

Overall, Babangida’s book may have evoked angry sentiments of an era that Nigerians would have wished never had been their lot but we now have an opportunity to go the whole log. As suggested by President Olusegun Obasanjo in his speech at the book launch, IBB should not be deterred by the knocks he is receiving for making this patriotic move in the twilight of his life. My friend and brother, Femi Fani-Kayode, who was barely six years old in 1966, could not possibly fault Ibrahim Badamasi Babangida, who was twenty four years old and already a commissioned officer in the Nigerian army by the time of the incidents under review. What FFK read as history, IBB witnessed as an event. So, Femi, my brother from another mother, don’t go there.